Lotty Rosenfeld

Entre o traço e o desvio

Inauguração

30 de agosto, 2025

11h-18h

30 de agosto –

25 de outubro, 2025

Zielinsky São Paulo

Entre o traço e o desvio

por Ana Roman

“A relação arte/política não significa dizer que a arte tematiza a política.

O trabalho da arte exige que repensemos a política.”¹

Dizem que apenas duas espécies na Terra trabalham juntas para transportar objetos maiores do que elas próprias: os humanos e as formigas. Num experimento recente², cientistas colocaram grupos de ambos diante do mesmo desafio: conduzir por um labirinto estreito um objeto em formato de T. Os humanos, privados de fala, hesitavam, erravam, repetiam atalhos inúteis. As formigas, ao contrário, mantinham a direção mesmo após colidir com paredes; recuavam até a entrada do beco sem saída e, sem perder o compasso, tentavam outra rota. Não havia líder nem plano prévio, apenas o que os cientistas chamaram de memória emergente, um saber tecido no deslocamento, que se transmitia entre corpos, capaz de evitar armadilhas e inventar passagens. Essa persistência silenciosa, coletiva, sem centro fixo é uma imagem que retorna quando penso no trabalho de Lotty Rosenfeld. Ela mesma construiu, ao longo de décadas, um percurso de trabalhos constituídos de desvios, interrupções e retomadas.

A lembrança da fileira de formigas descrita no estudo científico se mistura à imagem citada pela escritora Diamela Eltit ao comentar um trabalho mais recente da artista, Moción de Orden (2002)³. Diante do grande fluxo de formigas projetado em uma plataforma de petróleo, Eltit⁴ destaca o instante em que um dedo pode adentrar o caminho da projeção de imagem. A linha se quebra, o grupo se dispersa, a ordem se desfaz:

“A travessia das formigas pelas planícies de sólido concreto também está sujeita a múltiplas interferências. O dedo humano – aquele que aponta, ordena, decide – é o mesmo que bloqueia a passagem e semeia a desordem. O dedo do homem, de Deus, da criança onipotente está sempre pronto para desviar o curso traçado por um caminho. Porque o caminho das formigas não é, e nunca foi, fácil. O obstáculo está lá, espalhando o terror pelos trilhos. A epopeia formigueira – sempre carregando um fardo pesado e desmedido – será repetidamente interrompida e, com a mesma insistência, a multidão (essa formiga surgida de não se sabe onde) retorna à marcha com sua carga, empenhada em contornar o dedo ameaçador que, certeiro e inútil, provoca a ruptura e anuncia a recomposição do avanço⁵” [tradução nossa].

É no momento de suspensão, entre a interrupção e a reorganização, que Walter Benjamin⁶ localiza a possibilidade de um gesto político. Escovar a história a contrapelo, para ele, é deter o tempo homogêneo, abrir fissuras no curso aparente dos acontecimentos, mostrar que a marcha não é natural, mas construída, e que, portanto, pode ser desviada. A obra de Rosenfeld é, de muitas formas, um exercício contínuo para encontrar esse instante, esse espaço em que a lógica dominante se suspende e outro trajeto pode emergir.

Em 1979, sob a ditadura militar de Augusto Pinochet, Rosenfeld encontrou uma dessas fissuras no asfalto de Santiago. A cidade, então, era cenário de um projeto autoritário e neoliberal conduzido a ferro e fogo: ruas vigiadas, praças militarizadas, discursos oficiais repetidos na mídia controlada, enquanto a repressão invisível e sistemática calava e eliminava opositores. No espaço urbano, até as linhas pintadas no chão participavam do regime de controle. Foi sobre essas marcas aparentemente banais que Rosenfeld decidiu agir. Em Una Milla de Cruces sobre el Pavimento, ela transformou as linhas descontínuas que orientavam o trânsito em cruzes brancas: medidas em milhas, essas linhas evocavam tanto a padronização importada dos Estados Unidos, que era um país aliado do regime e modelo de sua economia, quanto a simbologia complexa da cruz: adição, fé, luto. No encontro entre traço contínuo e traço transversal, o espaço regulado se convertia em espaço de questionamento.

A ação conjugava precisão e insurgência: vê-se a artista ajoelhada no meio-fio, alinhando faixas no asfalto sob olhares de vigilância. O movimento, contido e milimétrico, instala a tensão: cada cruz é uma microinvasão na pele da cidade, deslocando o código que governa o cotidiano. Simples e arriscado, popular e cortante, o gesto reprograma o simbólico e o espacial, pois a cruz que se forma interrompe o curso, dobra o itinerário prescrito e ergue uma barricada mínima. Sua força não está na assinatura, mas na instabilidade do sinal e na ocupação do espaço comum por um traço quase anônimo, imediatamente legível.

Paralelamente, Rosenfeld integrou o Colectivo Acciones de Arte (CADA) com Diamela Eltit, Raúl Zurita, Juan Castillo e Fernando Balcells, concebendo a arte como ação direta no tecido social sob a ditadura de Pinochet⁷. Suas intervenções infiltravam poesia e crítica no cotidiano, ocupavam caminhões de leite, lançavam panfletos sobre a cidade e insinuavam-se na mídia com textos cifrados, sempre para reabrir o imaginário público em que a censura imperava. O CADA operava como um organismo coletivo que articulava performance, intervenção urbana e estratégias de comunicação, mas também como um laboratório de repetição e deslocamento, em que cada gesto retornava ao espaço comum e ganhava novos sentidos, conforme o contexto. Entre essas experiências, destacou-se No+, enunciado deliberadamente inacabado que convocava a participação popular: No+ fome, No+ repressão, No+ tortura. Mínimo, replicável e anônimo, o signo circulou por muros, cartazes e projeções, afirmando uma imaginação compartilhada em vez de uma autoria isolada. Esse programa sintetiza um capítulo decisivo da neovanguarda chilena, reconhecido por Nelly Richard como Escena de Avançada⁸.

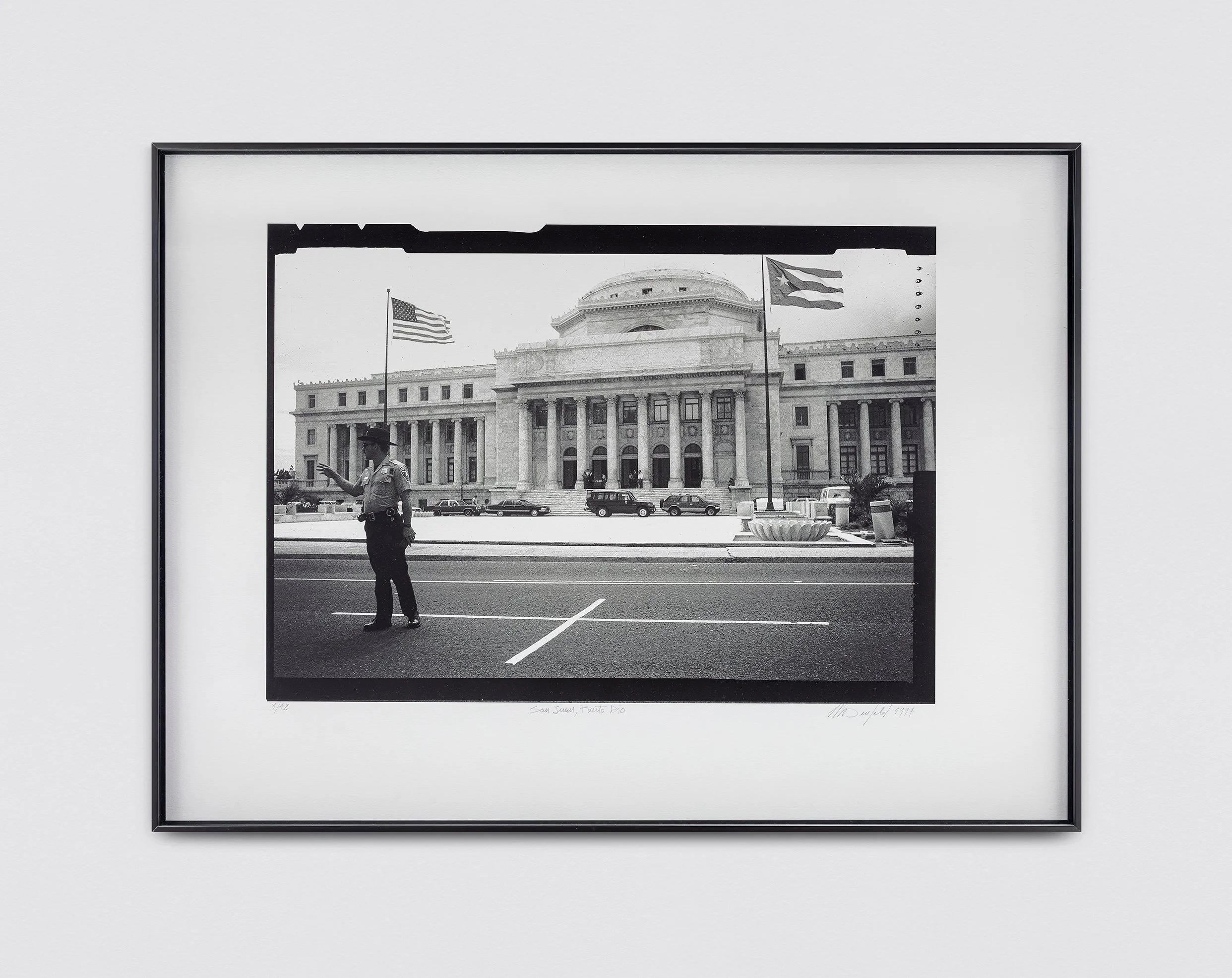

Ao longo dos anos, Rosenfeld reencenou Una Milla de Cruces em lugares de forte carga histórica: La Moneda, a Casa Branca, fronteiras nacionais, monumentos e ruas marcadas por conflito. A cada retorno, não repetia o gesto; deslocava-o. A cruz mudava de sentido, respondia ao entorno, acumulava memória e tensão. Essa insistência faz o passado agir no presente, como um clarão que interrompe a marcha e reabre o que parecia decidido. Ao reinscrever sinais em cenários distintos, a artista transforma a repetição em abertura. Em seus trabalhos individuais e em outros realizados em colaboração com o CADA, o foco dos trabalhos se desloca do eu e passa a atuar na busca de uma imaginação compartilhada, feminista⁹ e anticapitalista, capaz de operar no comum e abalar consensos. Nessa chave, a imaginação não se esgota¹⁰, pois, mesmo sob ditadura, colonialismo, patriarcado ou capitalismo, ninguém está totalmente cativo.

A maior parte das ações de Rosenfeld é capturada por fotografia, e isso não é detalhe técnico; é escolha de linguagem. A imagem fotográfica aparece como o instante suspenso em que o gesto ainda reverbera: o enquadramento condensa o antes e o depois da ação, fixa a cruz recém-inscrita no asfalto e, ao mesmo tempo, expõe a resistência do espaço que tenta absorvê-la. Por isso a artista recusa a noção de “registro” como algo secundário. A fotografia, em sua prática, funciona como obra autônoma e como suporte móvel de sentido. Ao circular em livros, paredes, jornais e projeções, ela desloca a intervenção do tempo da rua para um “presente constante”, reativando o conflito em cada nova aparição. Não se trata apenas de lembrar o que ocorreu, mas de reinstalar o atrito entre o signo e a ordem do lugar, como se cada cópia pudesse reabrir o ato e devolver ao público a experiência de interrupção.

Em El Empeño Latinoamericano (1998), esse método aparece com nitidez: imagens circulares de uma câmera de vigilância na casa de penhores La Tía Rica mostram pessoas que entram e saem para penhorar objetos de sobrevivência; a sequência é interceptada por números da Bolsa de Comércio de Santiago. O título joga com a ambiguidade entre empeñar (penhorar) e empeño (empenho/teimosia): a América Latina é uma região geopolítica que, empeñada y empeñosa, responde sem descanso à pressão do capitalismo em sua fase neoliberal.

O fluxo de imagens é organizado de modo a remeter a ideia de circulação infinita – de objetos, bens, corpos. A trilha, feita de sons guturais e ruídos indeterminados, não ilustra: sustenta a tensão e devolve espessura ao que a vigilância tenta achatar. Como escreveu a própria artista, “tenho pensado, e repensado, o som como elemento estruturador do trabalho… A voz testemunhal vem se entrelaçando à voz oficial para… colocar em cena a ‘outra versão’”¹¹. O som, assim, torna-se matéria política, capaz de rasgar a superfície lisa da imagem e aproximar regimes de verdade que costumam aparecer separados (financeiro, clínico, policial, íntimo).

Em Arritmia (1992), a montagem encadeia imagens de poder e repressão – polícia em formação, tribunais, prisões – em um looping que comprime e desloca sentidos. Monumentos caem, multidões se agitam, corpos correm e se ocultam; rostos cobertos entram em carros à saída de julgamentos; bandeiras e ícones dos Estados Unidos cruzam festividades em tom caricatural. As cenas retornam aceleradas e recortadas, sem resolução, como se a ordem se alimentasse da própria repetição. Não há protagonista, mas sim uma coreografia tensa entre sinais oficiais e gestos civis. Cada corte interrompe a continuidade e empurra o olhar para as bordas, onde o ruído emerge e a narrativa falha.

A trilha sonora opera como pastiche pop de super-herói, lembrando o Batman televisivo dos anos 1970 e convertendo-o em “badman” [homem mal]¹². O pulso de caixa seca, sintetizadores e riffs pegajosos situa o filme no clima sonoro do fim da década de 1970 e início da de 1980. A melodia adere às imagens duras e provoca um curto-circuito: o herói midiático se converte em anti-herói de Estado, e o brilho do entretenimento deixa à mostra seu fundo cínico. O ritmo repete e descompassa, instaurando o batimento irregular que lhe dá nome. O som não embala, mas estrutura e atrita, tornando audível a violência do espetáculo.

Em termos de produção de imagens¹³, Rosenfeld trabalha com um acervo heterogêneo de fotografias, vídeos próprios e materiais captados da televisão e de outras formas de circulação de mídia. Tudo é articulado pela montagem, que corta, aproxima, repete e desloca. Ela volta aos mesmos fragmentos anos depois e os faz dialogar com materiais novos. Em paralelo, documenta as exibições, filmando projeções em ruas, fachadas, plataformas e museus. Esses registros reaparecem em outras produções, de modo que o dispositivo que mostra a obra vira matéria do trabalho. O resultado é um arquivo vivo¹⁴, que se expande, se reescreve e volta a significar a cada contexto. Muitas imagens, oriundas de TV e VHS, conservam ruídos, compressões e legendas. Longe de ser um defeito, essa materialidade opera como conteúdo, pois torna visíveis a trajetória social da imagem e as disputas que a atravessam.

A produção de Lotty, vista da perspectiva de 2025, soa ainda mais urgente: sua obra usa o repertório visual do próprio mundo para desmontar os mecanismos que o fazem circular¹⁵. Como diz a artista, trata-se de “tomar uma imagem e levá-la ao seu extremo mais conflitivo”¹⁶, não para celebrar a globalização, mas para denunciar a violência dos sistemas que a regulam. Num tempo em que o neoliberalismo transforma a arte em espetáculo e o sujeito em consumidor, seu programa é ocupar o espaço público com imagens incômodas, capazes de fissurar a estética midiática, hoje amplificada por feeds e plataformas da internet cuja escala atual ela não chegou a testemunhar. É, enfim, uma busca pelo estabelecimento de certa política da imagem¹⁷: construir visualidades que resistam à fetichização de mercado e exponham as técnicas que uniformizam os sujeitos¹⁸.

Entre o traço e o desvio, entre o corte e a reorganização, Rosenfeld afirma uma política da imagem que não dita conclusões, mas expõe a arbitrariedade do que parece fixo. No Brasil, onde a disputa pelo espaço comum se acirra, da memória da ditadura às práticas de militarização e ao cerco publicitário das cidades, essa gramática da interrupção funciona como método de leitura e ação: reorienta o olhar, reabre passagens, desprograma sinais. Como as fileiras de formigas que, interrompidas, inventam novas rotas, suas obras mostram que a marcha coletiva pode ser reconfigurada diante do imprevisto. Cada cruz no asfalto, cada ruído que fere o silêncio e cada corte que quebra a sequência abrem a possibilidade de imaginar outros modos de habitar o comum, não como destino pré-traçado, mas como caminho inventado passo a passo.

___________

¹ ROSENFELD, Lotty; TALA, Alexia. Sinais dos tempos. Revista ZUM, n. 26, 20 jun. 2024. Disponível em: https://revistazum.com.br/revista-zum-26/sinais-dos-tempos/. Acesso em: 14 ago. 2025.

² G1. Formigas superam humanos em teste de inteligência coletiva; veja vídeo. g1, 17 mar. 2025. Disponível em: https://g1.globo.com/ciencia/noticia/2025/03/17/formigas-superam-humanos-em-teste-de-inteligencia-coletiva-veja-video.ghtml. Acesso em: 14 ago. 2025.

³ Moción de Orden (2002) é uma obra de vídeo em trânsito. Começa com a projeção noturna de uma fileira de formigas que cruza o círculo do heliponto de uma plataforma petrolífera no Estreito de Magalhães. A partir daí, o mesmo motivo reaparece em fachadas e interiores, no metrô, em muros e em caminhões, além de ocupar o Museu Nacional de Belas Artes, o Museu de Arte Contemporânea, a Galería Gabriela Mistral e o Centro Cívico de Santiago. Não se trata de um filme único nem de um objeto fixo: a instalação é recombinante, com múltiplas projeções, fotografias e fontes sonoras, sempre ajustadas à arquitetura do lugar. Ao sobrepor o enxame mínimo ao aparato do petróleo e a edifícios do Estado, a artista introduz ruído na ordem vigente e mostra que os códigos do espaço público podem ser interrompidos e refeitos. As formigas operam como metáfora de uma multidão que se desorganiza e se reorganiza, inventa rotas diante de obstáculos e sugere outros modos de circulação do comum.

⁴ ELTIT, Diamela. Arde Troya. In: LOTTY ROSENFELD: Moción de orden. Catálogo da exposição Moción de orden do Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes. Santiago: Ocho Libros Editores, 2003. p. 52.

⁵ No original: “(...) el viaje de las hormigas por las planicies de sólido concreto, también está expuesto a múltiples interferencias. El dedo humano, ese que indica, que ordena, que decide, va a ser aquel que impide el paso y siembra el desorden. El dedo del hombre, de Dios, del niño omnipotente, está presto a torcer los cursos que porta un camino. Porque el camino de las hormigas no es, ni nunca ha sido fácil. El escollo está allí, sembrando el terror en los senderos. La épica hormiguera – que siempre porta una carga pesada y excesiva – será de manera recurrente obstaculizada y, en forma igualmente recurrente, lo multitudinario (esa hormiga salida de no se sabe dónde) vuelve a la carga con su carga para conseguir sortear el acechante dedo, que, certero e inútil, produce la ruptura y anuncia la recomposición de la marcha”.

⁶ BENJAMIN, Walter. Sobre o conceito de história: edição crítica. Organização e tradução de Adalberto Müller e Márcio Seligmann-Silva. São Paulo: Alameda Casa Editorial, 2020. 208 p. (livrarialoyola.com.br, pt.wikipedia.org)

⁷ As ações do CADA ressoam fortemente no contexto brasileiro e no que a curadoria de Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin (Queens Museum, 1999) chamou de conceitualismos do Sul. Ali, Luiz Camnitzer, Jane Farver e Rachel Weiss distinguiram “arte conceitual” (de corte mais formalista, alinhada ao minimalismo euro-norte-americano) de conceitualismo, entendido como um conjunto de práticas que, entre os anos 1950–1980, alarga o campo da arte: desmaterializa o objeto (deslocando seu sentido e reinvestindo significados em objetos e signos preexistentes), prática crítica institucional, engaja-se diretamente na vida pública e na política e enfatiza linguagem e circulação.

⁸ RICHARD, Nelly. La insubordinación de los signos. Santiago: Ediciones Cuarto Propio, 1994.

⁹ FLORES, Mariairis; GIUNTA, Andrea. Arte, género y feminismo en torno al trabajo de Lotty Rosenfeld: conversación. In: LOTTY ROSENFELD: ENTRECRUCES DE LA MEMORIA (1979–2020). Buenos Aires: Parque de la Memoria; Embajada de Chile – Centro Cultural Matta; Fundación Lotty Rosenfeld, 2024. Catálogo de exposição.

¹⁰ RICHARD, Nelly. Activar la imaginación crítica en torno a los signos: de una sola línea. In: LOTTY ROSENFELD: ENTRECRUCES DE LA MEMORIA (1979–2020). Buenos Aires: Parque de la Memoria; Embajada de Chile – Centro Cultural Matta; Fundación Lotty Rosenfeld, 2024. Catálogo de exposição.

¹¹ No original: "he pensado y repensado el sonido como instrumento estructurador de obra… La voz testimonial se ha interconectado con la voz oficial para… poner en escena la ‘otra versión’”. Excerto de documento pertencente a Fundación Lotty Rosenfeld.

¹² É possível ouvir a introdução do Batman no seguinte link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EtoMN_xi-AM

¹³ Para saber mais sobre a produção de imagens da artista: ROJAS, Sergio. El cuerpo de los signos. In: ROSENFELD, Lotty. Moción de orden [catálogo de exposição]. Santiago de Chile: Galería Gabriela Mistral, 2002. p. 4–37. Disponível em: https://repositorio.cultura.gob.cl/bitstream/handle/123456789/5068/Lotty%20Rosenfeld.PDF?isAllowed=y&sequence=1. Acesso em: 14 ago. 2025.

¹⁴ Por falar em arquivos, vale retomar o trabalho da Fundación Lotty Rosenfeld (Santiago, 2021). Entidade privada sem fins lucrativos criada pelos filhos da artista, a fundação dedica-se a conservar, expor e difundir sua obra e seus arquivos. O Arquivo Lotty Rosenfeld reúne cerca de 25 metros lineares de documentação produzida entre 1968 e 2020 (correspondência com artistas e curadores, registros fotográficos e audiovisuais, projetos, catálogos e folhetos), organizado em um fundo único da artista. Trata-se de um acervo aberto e em expansão, mobilizado por exposições e projetos que atestam a vigência e a relevância de seu legado. A maior parte dos documentos usados para escrever este texto foram consultados na plataforma online da instituição. Acesso em: https://fundacionlottyrosenfeld.org/

¹⁵ Para uma reflexão sobre o papel da arte na contemporaneidade, ver breve relato da artista em: TALA, Alexia. How Chilean Artist Lotty Rosenfeld Created an Enduring Protest Symbol. ArtReview, 13 out. 2020. Disponível em: https://artreview.com/how-chilean-artist-lotty-rosenfeld-created-an-enduring-protest-symbol/. Acesso em: 14 ago. 2025.

¹⁶ No original: "Tomar una imagen y llevarla hasta su extremo más conflictivo." Excerto retirado do documento Intención de obra 1 - Integrante do acervo da Fundación Lotty Rosenfeld.

¹⁷ Ver reflexões sobre esse assunto em: BRIZUELA, Natalia; BRYAN-WILSON, Julia. Speaking of Lotty Rosenfeld: “Gestures Dangerous, Simple, and Popular”. October, v. 176, p. 111–137, Spring 2021. DOI: 10.1162/octo_a_00429. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1162/octo_a_00429. Acesso em: 14 ago. 2025.

¹⁸ Nas palavras da artista: “El neoliberalismo promueve formas de arte que tienden al espectáculo, pienso que lo importante y lo productivo en medio de esta situación es poner en el espacio público producciones artísticas incomodas y rebeldes a las operaciones de mercado.” Excerto retirado do documento Intención de obra 1 - Integrante do acervo da Fundación Lotty Rosenfeld.

Lotty Rosenfeld

Between the trace and the deviation

Opening

August 30, 2025

11am-6pm

August 30 –

October 25, 2025

Zielinsky São Paulo

Between the trace and the deviation

by Ana Roman

“The relation art/politics does not mean saying that art simply addresses politics.

The work of art demands that we rethink politics.”¹

It is said that only two species work together on Earth to carry objects larger than themselves: humans and ants. In a recent experiment², scientists have placed both species in front of the same challenge: to carry an object through a narrow maze shaped like a T. Humans, deprived of speech, hesitated, stumbled, repeating useful shortcuts. Ants, nevertheless, maintained their direction even after colliding on the walls; they would retreat to the entrance of the dead end and, without losing their sense of orientation, try another route. There was no leader nor prior plan, only what scientists would call emergent memory, a knowledge built displacement, transiting between bodies, capable of avoiding traps and creating paths. This silent, collective persistence — without a fixed center — is an image that returns to me when I think about the work of Lotty Rosenfeld. She herself constructed, over decades, a trajectory of works shaped by detours, interruptions, and returns.

The memory of the line of ants described in the scientific study blends with the image evoked by writer Diamela Eltit when reflecting on a more recent work by the artist, Moción de Orden (2002)³. Confronted with the dense flow of ants projected onto an oil platform, Eltit⁴ draws attention to the moment when a finger can enter the path of the image projection. The line breaks, the group scatters, the order falls apart:

“The ants’ crossing over plains of solid concrete is also subject to multiple interferences. The human finger — the one that points, commands, decides — is the same one that blocks the passage and sows disorder. The finger of man, of God, of the omnipotent child is always ready to divert the path that has been traced. For the path of the ants is not, and has never been, easy. The obstacle is there, spreading terror across the tracks. The ant epic — always carrying a burden both heavy and disproportionate — will be repeatedly interrupted, and with the same persistence, the multitude (this ant that appears from who knows where) resumes its march with its load, determined to go around the threatening finger that, precise and useless, causes rupture and signals the recomposition of forward movement”.⁵

It is in the moment of suspension, between the interruption and the reorganization, that Walter Benjamin⁶ locates the possibility of a political gesture. To brush history against the grain, for him, is to arrest homogeneous time, to open fissures in the apparent course of events, to show that the march is not natural but constructed, and therefore can be diverted. Rosenfeld’s work is, in many ways, a continuous exercise to find that instant, that space where the dominant logic is suspended and another path can emerge

In 1979, under Augusto Pinochet’s military dictatorship, Rosenfeld found one of those fissures in the asphalt of Santiago. The city was then the stage for an authoritarian and neoliberal project carried out with iron and fire: watched streets, militarized plazas, official speeches repeated in controlled media, while invisible and systematic repression silenced and eliminated opponents. In the urban space, even the lines painted on the ground participated in the regime of control. It was on these seemingly banal marks that Rosenfeld decided to act. In Una Milla de Cruces sobre el Pavimento, she transformed the dashed lines that guided traffic into white crosses: measured in miles, these lines evoked both the standardization imported from the United States, which was an ally of the regime and a model for its economy, and the complex symbolism of the cross: addition, faith, mourning. At the meeting point between continuous and transversal lines, the regulated space was transformed into a space of questioning.

The action combined precision and insurgency: the artist can be seen kneeling on the curb, aligning stripes on the asphalt under watchful eyes. The movement, restrained and meticulous, creates tension: each cross is a micro-invasion on the city’s surface, displacing the code that governs everyday life. Simple and risky, popular and sharp, the gesture reprograms the symbolic and the spatial, for the cross that forms interrupts the flow, bends the prescribed route, and raises a minimal barricade. Its strength lies not in the signature, but in the instability of the sign and the occupation of common space by an almost anonymous mark, immediately legible.

In parallel, Rosenfeld joined the Colectivo Acciones de Arte (CADA) alongside Diamela Eltit, Raúl Zurita, Juan Castillo, and Fernando Balcells, conceiving art as direct action within the social fabric under Pinochet’s dictatorship⁷. Her interventions infused poetry and critique into everyday life, occupying milk trucks, distributing pamphlets throughout the city, and insinuating themselves into the media with coded texts—always aiming to reopen the public imagination where censorship prevailed. CADA operated as a collective organism that combined performance, urban intervention, and communication strategies, but also as a laboratory of repetition and displacement, where each gesture returned to the common space and gained new meanings depending on the context. Among these experiences, No+ stood out—a deliberately unfinished slogan that called for popular participation: No+ hunger, No+ repression, No+ torture. Minimal, replicable, and anonymous, the sign circulated on walls, posters, and projections, affirming a shared imagination rather than isolated authorship. This program encapsulates a decisive chapter of the Chilean neo-avant-garde, recognized by Nelly Richard as the Escena de Avanzada⁸.

Over the years, Rosenfeld reenacted Una Milla de Cruces in places with strong historical significance: La Moneda, the White House, national borders, monuments, and streets marked by conflict. With each return, she did not repeat the gesture; she displaced it. The cross changed its meaning, responded to its surroundings, and accumulated memory and tension. This persistence makes the past act in the present, like a flash that interrupts the march and reopens what seemed decided. By reinscribing signs in different settings, the artist transforms repetition into openness. In her individual works and those created in collaboration with CADA, the focus shifts from the self to the pursuit of a shared, feminist⁹, and anti-capitalist imagination, being capable of operating within the common and shaking consensuses. In this key, imagination does not run dry¹⁰, for even under dictatorship, colonialism, patriarchy, or capitalism, no one is ever completely captive.

Most of Rosenfeld´s actions are captured by photography, and it is not a mere technical detail; it´s a matter of language. The photographic image appears as a suspended moment in which the gesture still resonates: the framing condenses the before and after of the action, fixes the newly inscribed cross on the asphalt, and at the same time exposes the resistance of the space trying to absorb it. For this reason, the artist rejects the notion of “documentation” as something secondary. In her practice, photography functions both as an autonomous work and as a mobile carrier of meaning. By circulating through books, walls, newspapers, and projections, it displaces the intervention from the street’s time to a “constant present,” reactivating the conflict with each new appearance. It is not merely about remembering what happened but about reinstalling the friction between the sign and the order of the place, as if each copy could reopen the act and return to the public the experience of interruption.

In El Empeño Latinoamericano (1998), this method is clearly evident: circular images from a surveillance camera at the La Tía Rica pawnshop show people coming and going to pawn survival items; the sequence is interrupted by numbers from the Santiago Stock Exchange. The title plays with the ambiguity between empeñar (to pawn) and empeño (commitment): Latin America is a geopolitical region that, committed and stubborn, responds tirelessly to the pressure of capitalism in its neoliberal phase.

The flow of images is organized to evoke the idea of infinite circulation—of objects, goods, bodies. The soundtrack, made up of guttural sounds and indistinct noises, does not illustrate; it sustains the tension and restores depth to what surveillance tries to flatten. As the artist herself wrote, “I have thought, and reconsidered, sound as a structuring element of the work… The testimonial voice intertwines with the official voice to… stage the ‘other version.’”¹¹. Sound thus becomes political material, capable of tearing through the smooth surface of the image and bringing closer regimes of truth that usually appear separated (financial, clinical, police, intimate).

In Arritmia (1992), the editing sequences images of power and repression—police formations, courts, prisons—in a loop that compresses and displaces meanings. Monuments fall, crowds stir, bodies run and hide; covered faces get into cars after trials; flags and icons of the United States cross festivities in a caricatural tone. The scenes return accelerated and fragmented, without resolution, as if order feeds on its own repetition. There is no protagonist, but rather a tense choreography between official signs and civil gestures. Each cut interrupts continuity and pushes the gaze toward the edges, where noise emerges and the narrative fails.

The soundtrack functions as a pop superhero pastiche, recalling the 1970s TV Batman and turning him into a “badman”¹². The pulse of snare drums, synthesizers, and catchy riffs situates the film in the sonic atmosphere of the late 1970s and early 1980s. The melody adheres to the harsh images and triggers a short circuit: the media hero becomes a state anti-hero, and the shine of entertainment exposes its cynical core. The rhythm repeats and falls out of sync, establishing the irregular beat that gives the film its name. The sound does not soothe but structures and agitates, making the violence of the spectacle audible.

In terms of image production¹³, Rosenfeld works in a heterogeneous collection of photographs, her own videos and materials captured from television and other forms of media circulation. Everything is articulated through editing, which cuts, zooms in, repeats, and shifts. She returns to the same fragments years later and makes them dialogue with new material. At the same time, she would document her exhibitions, filming projections on the streets, building façades, platforms and museums. Those registrations reappear in other works, so that the device that displays the work becomes part of the work itself. The result is a living file¹⁴, which expands, rewrites itself, and takes on new meaning in each context. Many of the images, sourced from TV and VHS, retain noise, compression artifacts, and subtitles. Far from being a flaw, this materiality functions as content, as it makes visible the social trajectory of the image and the conflicts that run through it.

Lotty’s work, seen from the perspective of 2025, feels even more urgent: her practice uses the visual repertoire of the world itself to dismantle the very mechanisms that keep it in circulation¹⁵. It’s about seizing an image and carrying it to its most charged, conflicted edge”¹⁶, not to celebrate globalization, but to denounce violence that systems regulate. In a time when neoliberalism turns art into spectacle and the subject into a mere consumer, her program is to occupy public space with unsettling images capable of fracturing the media aesthetic—now amplified by internet feeds and platforms on a scale she did not live to witness. It is, after all, a search for establishment of certain politics of image¹⁷: to build visualities that resist the fetishization of market and exposes techniques that uniformalize subjects¹⁸.

Between the trace and the devination, between cut and reorganization, Rosenfeld affirms an image politics that does not dictates conducts, but exposes arbitrariness that appears in what is fixed. In Brazil, where the struggle for common space intensifies—from the memory of the dictatorship to practices of militarization and the advertising siege of cities—this grammar of interruption functions as both a method of reading and of action: it reorients the gaze, reopens pathways, and deprograms signals. Like rows of ants that, when interrupted, invent new routes, their works show that collective movement can be reconfigured in the face of the unexpected. Each cross on the asphalt, each noise that pierces silence, and each cut that breaks sequence opens up the possibility of imagining other ways of inhabiting the common—not as a predetermined fate, but as a path invented step by step.

___________

¹ ROSENFELD, Lotty; TALA, Alexia. Signs of the times (Sinais dos tempos) . Revista ZUM, n. 26, 20 jun. 2024. Avaliable in: https://revistazum.com.br/revista-zum-26/sinais-dos-tempos/. Access in: August 14, 2025.

² G1. Ants outperform humans in collective intelligence test (Formigas superam humanos em teste de inteligência coletiva); watch the video. g1, 17 march 2025. Avaliable in: https://g1.globo.com/ciencia/noticia/2025/03/17/formigas-superam-humanos-em-teste-de-inteligencia-coletiva-veja-video.ghtml. Access in: 14 august, 2025.

³ Moción de Orden (2002) is a video work in transit. It begins with the nighttime projection of a line of ants crossing the helipad circle of an oil platform in the Strait of Magellan. From there, the same motif reappears on facades and interiors, in the subway, on walls and trucks, as well as occupying the National Museum of Fine Arts, the Museum of Contemporary Art, the Gabriela Mistral Gallery, and the Civic Center of Santiago. It is not a single film nor a fixed object: the installation is recombinant, with multiple projections, photographs, and sound sources, always adapted to the architecture of the site. By overlaying the minimal swarm onto the oil apparatus and State buildings, the artist introduces noise into the prevailing order and shows that the codes of public space can be interrupted and reconfigured. The ants function as a metaphor for a crowd that disorganizes and reorganizes itself, invents paths in the face of obstacles, and suggests alternative ways of circulating the commons.

⁴ ELTIT, Diamela. Arde Troya. In: LOTTY ROSENFELD: Moción de orden. Moción de orden do Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes exhibition catalog. Santiago: Ocho Libros Editores, 2003. p. 52.

⁵ In the original: “(...) el viaje de las hormigas por las planicies de sólido concreto, también está expuesto a múltiples interferencias. El dedo humano, ese que indica, que ordena, que decide, va a ser aquel que impide el paso y siembra el desorden. El dedo del hombre, de Dios, del niño omnipotente, está presto a torcer los cursos que porta un camino. Porque el camino de las hormigas no es, ni nunca ha sido fácil. El escollo está allí, sembrando el terror en los senderos. La épica hormiguera – que siempre porta una carga pesada y excesiva – será de manera recurrente obstaculizada y, en forma igualmente recurrente, lo multitudinario (esa hormiga salida de no se sabe dónde) vuelve a la carga con su carga para conseguir sortear el acechante dedo, que, certero e inútil, produce la ruptura y anuncia la recomposición de la marcha”.

⁶ BENJAMIN, Walter. On the Concept of History: Critical Edition. Edited and translated by Adalberto Müller and Márcio Seligmann-Silva. São Paulo: Alameda Casa Editorial, 2020. p. 208. (livrarialoyola.com.br, pt.wikipedia.org)

⁷ CADA’s actions strongly resonate within the Brazilian context and in what the curators of Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin (Queens Museum, 1999) called ´Conceptualisms of the south'. There, Luiz Camnitzer, Jane Farver, and Rachel Weiss distinguished 'conceptual art'—more formalist in character and aligned with Euro-North American minimalism—from 'conceptualism,' understood as a set of practices that, between the 1950s and 1980s, expanded the field of art: dematerializing the object (displacing its meaning and reinvesting significance in pre-existing objects and signs), engaging in critical institutional practices, directly involving itself in public life and politics, and emphasizing language and circulation.

⁸ RICHARD, Nelly. La insubordinación de los signos. Santiago: Ediciones Cuarto Propio, 1994.

⁹ FLORES, Mariairis; GIUNTA, Andrea. Art, Gender, and Feminism in Relation to the Work of Lotty Rosenfeld: Conversation. In: LOTTY ROSENFELD: INTERSECTIONS OF MEMORY (1979–2020). Buenos Aires: Parque de la Memoria; Embassy of Chile – Cultural Matta Center; Lotty Rosenfeld Foundation, 2024. Exhibition catalog.

¹⁰ RICHARD, Nelly. Activating Critical Imagination Around Signs: From a Single Line. In: LOTTY ROSENFELD: INTERSECTIONS OF MEMORY (1979–2020). Buenos Aires: Parque de la Memoria; Embassy of Chile – Cultural Matta Center; Lotty Rosenfeld Foundation, 2024. Exhibition catalog.

¹¹ In the original: “I have thought and reconsidered sound as a structuring instrument of the work… The testimonial voice has interconnected with the official voice to… stage the ‘other version.’” Excerpt from a document belonging to the Lotty Rosenfeld Foundation.

¹² You can check Batman´s introduction theme here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EtoMN_xi-AM

¹³ More about the artist´s production: ROJAS, Sergio. El cuerpo de los signos. In: ROSENFELD, Lotty. Moción de orden [exhibition catalog]. Santiago de Chile: Gabriela Mistral Gallery, 2002. p. 4–37. Avaliable in: https://repositorio.cultura.gob.cl/bitstream/handle/123456789/5068/Lotty%20Rosenfeld.PDF?isAllowed=y&sequence=1. Access in: August 14, 2025.

¹⁴ Speaking of archives, it is worth revisiting the work of the Fundación Lotty Rosenfeld (Santiago, 2021). A private, non-profit entity created by the artist’s children, the foundation is dedicated to preserving, exhibiting, and disseminating her work and archives. The Lotty Rosenfeld Archive holds approximately 25 linear meters of documentation produced between 1968 and 2020 (correspondence with artists and curators, photographic and audiovisual records, projects, catalogs, and leaflets), organized as a single archival collection dedicated to the artist. It is an open and expanding archive, activated by exhibitions and projects that attest to the ongoing relevance of her legacy. Most of the documents used to write this text were accessed through the institution’s online platform. Access at: https://fundacionlottyrosenfeld.org/

¹⁵ For a reflection of the artist´s role in contemporaneity, check artist´s speech: TALA, Alexia. How Chilean Artist Lotty Rosenfeld Created an Enduring Protest Symbol. ArtReview. august 14 2025. Avaliable in: https://artreview.com/how-chilean-artist-lotty-rosenfeld-created-an-enduring-protest-symbol/. Access in: august 14, 2025.

¹⁶ Originally: "Tomar una imagen y llevarla hasta su extremo más conflictivo." Taken from Intención de obra 1 document - in the collection of Fundación Lotty Rosenfeld.

¹⁷ As the artist said: “El neoliberalismo promueve formas de arte que tienden al espectáculo, pienso que lo importante y lo productivo en medio de esta situación es poner en el espacio público producciones artísticas incomodas y rebeldes a las operaciones de mercado.” Taken from Intención de obra 1 document - in the collection of Fundación Lotty Rosenfeld.

¹⁸ As the artist, herself, said: “El neoliberalismo promueve formas de arte que tienden al espectáculo, pienso que lo importante y lo productivo en medio de esta situación es poner en el espacio público producciones artísticas incomodas y rebeldes a las operaciones de mercado.” Taken from Intención de obra 1 document - in the collection of Fundación Lotty Rosenfeld.

Lotty Rosenfeld

Entre el trazo y el desvío

Inauguración

30 de Agosto, 2025

11h-18h

30 de Agosto –

25 de Octubre, 2025

Zielinsky São Paulo

Entre el trazo y el desvío

por Ana Roman

“La relación arte/política no significa decir que el arte tematiza la política.

El trabajo del arte exige que repensemos la política.”¹

Dicen que solo dos especies en la Tierra trabajan juntas para transportar objetos más grandes que ellas mismas: los humanos y las hormigas. En un experimento reciente², los científicos colocaron a grupos de ambos frente al mismo desafío: conducir por un laberinto estrecho un objeto en forma de T. Los humanos, privados de habla, dudaban, se equivocaban, repetían atajos inútiles. Las hormigas, en cambio, mantenían la dirección incluso después de chocar contra las paredes; retrocedían hasta la entrada del callejón sin salida y, sin perder el compás, intentaban otra ruta. No había líder ni plan previo, solo lo que los científicos llamaron memoria emergente, un saber tejido en el desplazamiento, que se transmitía entre cuerpos, capaz de evitar trampas e inventar pasajes. Esa persistencia silenciosa, colectiva, sin centro fijo, es una imagen que regresa cuando pienso en el trabajo de Lotty Rosenfeld. Ella misma construyó, a lo largo de décadas, un recorrido de obras constituidas por desvíos, interrupciones y retomadas.

El recuerdo de la fila de hormigas descrita en el estudio científico se mezcla con la imagen citada por la escritora Diamela Eltit al comentar una obra más reciente de la artista, Moción de Orden (2002)³. Ante el gran flujo de hormigas proyectado en una plataforma petrolera, Eltit destaca el instante en que un dedo puede adentrarse en el camino de la proyección de la imagen. La línea se quiebra, el grupo se dispersa, el orden se deshace:

“[...] el viaje de las hormigas por las planicies de sólido concreto, también está expuesto a múltiples interferencias. El dedo humano, ese que indica, que ordena, que decide, va a ser aquel que impide el paso y siembra el desorden. El dedo del hombre, de Dios, del niño omnipotente, está presto a torcer los cursos que porta un camino. Porque el camino de las hormigas no es, ni nunca ha sido fácil. El escollo está allí, sembrando el terror en los senderos. La épica hormiguera – que siempre porta una carga pesada y excesiva – será de manera recurrente obstaculizada y, en forma igualmente recurrente, lo multitudinario (esa hormiga salida de no se sabe dónde) vuelve a la carga con su carga para conseguir sortear el acechante dedo, que, certero e inútil, produce la ruptura y anuncia la recomposición de la marcha.”

Es en el momento de suspensión, entre la interrupción y la reorganización, donde Walter Benjamin localiza la posibilidad de un gesto político. Cepillar la historia a contrapelo, para él, es detener el tiempo homogéneo, abrir fisuras en el curso aparente de los acontecimientos, mostrar que la marcha no es natural, sino construida, y que, por lo tanto, puede ser desviada. La obra de Rosenfeld es, de muchas maneras, un ejercicio continuo para encontrar ese instante, ese espacio en que la lógica dominante se suspende y otro trayecto puede emerger.

En 1979, bajo la dictadura militar de Augusto Pinochet, Rosenfeld encontró una de esas fisuras en el asfalto de Santiago. La ciudad, entonces, era escenario de un proyecto autoritario y neoliberal conducido a sangre y fuego: calles vigiladas, plazas militarizadas, discursos oficiales repetidos en los medios controlados, mientras la represión invisible y sistemática silenciaba y eliminaba a los opositores. En el espacio urbano, hasta las líneas pintadas en el suelo participaban del régimen de control. Fue sobre esas marcas aparentemente banales que Rosenfeld decidió actuar. En Una Milla de Cruces sobre el Pavimento, transformó las líneas discontinuas que orientaban el tránsito en cruces blancas: medidas en millas, esas líneas evocaban tanto la estandarización importada de Estados Unidos —país aliado del régimen y modelo de su economía— como la simbología compleja de la cruz: adición, fe, luto. En el encuentro entre trazo continuo y trazo transversal, el espacio regulado se convertía en espacio de cuestionamiento.

La acción conjugaba precisión e insurgencia: se ve a la artista arrodillada en el borde de la acera, alineando franjas en el asfalto bajo miradas de vigilancia. El movimiento, contenido y milimétrico, instala la tensión: cada cruz es una microinvasión en la piel de la ciudad, desplazando el código que gobierna lo cotidiano. Simple y arriesgado, popular y cortante, el gesto reprograma lo simbólico y lo espacial, pues la cruz que se forma interrumpe el curso, dobla el itinerario prescrito y levanta una barricada mínima. Su fuerza no está en la firma, sino en la inestabilidad del signo y en la ocupación del espacio común por un trazo casi anónimo, inmediatamente legible.

Paralelamente, Rosenfeld integró el Colectivo Acciones de Arte (CADA) junto a Diamela Eltit, Raúl Zurita, Juan Castillo y Fernando Balcells, concibiendo el arte como acción directa en el tejido social bajo la dictadura de Pinochet.⁴ Sus intervenciones infiltraban poesía y crítica en lo cotidiano, ocupaban camiones de leche, lanzaban panfletos sobre la ciudad y se insinuaban en los medios con textos cifrados, siempre para reabrir el imaginario público en el que imperaba la censura. El CADA operaba como un organismo colectivo que articulaba performance, intervención urbana y estrategias de comunicación, pero también como un laboratorio de repetición y desplazamiento, en el que cada gesto retornaba al espacio común y adquiría nuevos sentidos, según el contexto. Entre esas experiencias, se destacó No+, enunciado deliberadamente inconcluso que convocaba la participación popular: No+ hambre, No+ represión, No+ tortura. Mínimo, replicable y anónimo, el signo circuló por muros, carteles y proyecciones, afirmando una imaginación compartida en lugar de una autoría aislada. Ese programa sintetiza un capítulo decisivo de la neovanguardia chilena, reconocida por Nelly Richard como Escena de Avanzada.⁵

A lo largo de los años, Rosenfeld reescenificó Una Milla de Cruces en lugares de fuerte carga histórica: La Moneda, la Casa Blanca, fronteras nacionales, monumentos y calles marcadas por el conflicto. En cada retorno, no repetía el gesto; lo desplazaba. La cruz cambiaba de sentido, respondía al entorno, acumulaba memoria y tensión. Esa insistencia hace que el pasado actúe en el presente, como un destello que interrumpe la marcha y reabre lo que parecía decidido. Al reinscribir signos en escenarios distintos, la artista transforma la repetición en apertura. En sus trabajos individuales y en otros realizados en colaboración con el CADA, el foco de las obras se desplaza del yo y pasa a operar en la búsqueda de una imaginación compartida, feminista⁶ y anticapitalista, capaz de actuar en lo común y sacudir consensos. En esta clave, la imaginación no se agota⁷, pues, incluso bajo dictadura, colonialismo, patriarcado o capitalismo, nadie está completamente cautivo.

La mayor parte de las acciones de Rosenfeld se captura mediante fotografía, y eso no es un detalle técnico; es una elección de lenguaje. La imagen fotográfica aparece como el instante suspendido en que el gesto aún reverbera: el encuadre condensa el antes y el después de la acción, fija la cruz recién inscrita en el asfalto y, al mismo tiempo, expone la resistencia del espacio que intenta absorberla. Por ello, la artista rechaza la noción de “registro” como algo secundario. La fotografía, en su práctica, funciona como obra autónoma y como soporte móvil de sentido. Al circular en libros, muros, periódicos y proyecciones, desplaza la intervención del tiempo de la calle a un “presente constante”, reactivando el conflicto en cada nueva aparición. No se trata solo de recordar lo que ocurrió, sino de reinstalar la fricción entre el signo y el orden del lugar, como si cada copia pudiera reabrir el acto y devolver al público la experiencia de la interrupción.

En El Empeño Latinoamericano (1998), este método aparece con nitidez: imágenes circulares de una cámara de vigilancia en la casa de empeños La Tía Rica muestran personas que entran y salen para empeñar objetos de supervivencia; la secuencia es interceptada por números de la Bolsa de Comercio de Santiago. El título juega con la ambigüedad entre empeñar (empeñar) y empeño (empeño/terquedad): América Latina es una región geopolítica que, empeñada y empeñosa, responde sin descanso a la presión del capitalismo en su fase neoliberal.

El flujo de imágenes se organiza de manera que remite a la idea de circulación infinita —de objetos, bienes, cuerpos. La banda sonora, compuesta de sonidos guturales y ruidos indeterminados, no ilustra: sostiene la tensión y devuelve espesor a lo que la vigilancia intenta aplanar. Como escribió la propia artista: "he pensado y repensado el sonido como instrumento estructurador de obra… La voz testimonial se ha interconectado con la voz oficial para… poner en escena la ‘otra versión’”⁸. El sonido, así, se convierte en materia política, capaz de rasgar la superficie lisa de la imagen y acercar regímenes de verdad que suelen aparecer separados (financiero, clínico, policial, íntimo).

En Arritmia (1992), la montaje encadena imágenes de poder y represión —policía en formación, tribunales, prisiones— en un bucle que comprime y desplaza sentidos. Los monumentos caen, las multitudes se agitan, los cuerpos corren y se ocultan; rostros cubiertos entran en autos al salir de los juicios; banderas e íconos de Estados Unidos cruzan festividades en tono caricaturesco. Las escenas regresan aceleradas y recortadas, sin resolución, como si el orden se alimentara de la propia repetición. No hay protagonista, sino una coreografía tensa entre señales oficiales y gestos civiles. Cada corte interrumpe la continuidad y empuja la mirada hacia los bordes, donde emerge el ruido y la narrativa falla.

La banda sonora funciona como un pastiche pop de superhéroe, recordando al Batman televisivo de los años 1970 y convirtiéndolo en “badman” [hombre malo]⁹. El pulso de caja seca, sintetizadores y riffs pegajosos sitúa el video en el clima sonoro de fines de la década de 1970 y comienzos de 1980. La melodía se adhiere a las imágenes duras y provoca un cortocircuito: el héroe mediático se convierte en antihéroe del Estado, y el brillo del entretenimiento deja al descubierto su trasfondo cínico. El ritmo se repite y descompasa, instaurando el latido irregular que le da nombre. El sonido no arrulla, sino que estructura y fricciona, haciendo audible la violencia del espectáculo.

En términos de producción de imágenes¹⁰, Rosenfeld trabaja con un acervo heterogéneo de fotografías, videos propios y materiales captados de la televisión y de otras formas de circulación mediática. Todo se articula mediante el montaje, que corta, acerca, repite y desplaza. Vuelve a los mismos fragmentos años después y los hace dialogar con materiales nuevos. Paralelamente, documenta las exhibiciones, filmando proyecciones en calles, fachadas, plataformas y museos. Esos registros reaparecen en otras producciones, de modo que el dispositivo que muestra la obra se convierte en materia del trabajo. El resultado es un archivo vivo¹¹, que se expande, se reescribe y vuelve a significar en cada contexto. Muchas imágenes, provenientes de TV y VHS, conservan ruidos, compresiones y subtítulos. Lejos de ser un defecto, esta materialidad opera como contenido, pues hace visibles la trayectoria social de la imagen y las disputas que la atraviesan.

La producción de Lotty, vista desde la perspectiva de 2025, suena aún más urgente: su obra utiliza el repertorio visual del propio mundo para desmontar los mecanismos que lo hacen circular¹². Como dice la artista, se trata de “tomar una imagen y llevarla hasta su extremo más conflictivo”¹³, no para celebrar la globalización, sino para denunciar la violencia de los sistemas que la regulan. En un tiempo en que el neoliberalismo transforma el arte en espectáculo y al sujeto en consumidor, su programa consiste en ocupar el espacio público con imágenes incómodas, capaces de fisurar la estética mediática, hoy amplificada por feeds y plataformas de internet cuya escala actual ella no llegó a presenciar. Es, en definitiva, una búsqueda por el establecimiento de cierta política de la imagen¹⁴: construir visualidades que resistan la fetichización del mercado y expongan las técnicas que uniformizan a los sujetos.¹⁵

Entre el trazo y el desvío, entre el corte y la reorganización, Rosenfeld afirma una política de la imagen que no dicta conclusiones, sino que expone la arbitrariedad de lo que parece fijo. En Brasil, donde la disputa por el espacio común se intensifica, desde la memoria de la dictadura hasta las prácticas de militarización y el cerco publicitario de las ciudades, esta gramática de la interrupción funciona como método de lectura y acción: reorienta la mirada, reabre pasajes, desprograma señales. Como las filas de hormigas que, interrumpidas, inventan nuevas rutas, sus obras muestran que la marcha colectiva puede reconfigurarse ante lo imprevisto. Cada cruz en el asfalto, cada ruido que hiere el silencio y cada corte que rompe la secuencia abren la posibilidad de imaginar otros modos de habitar lo común, no como destino preestablecido, sino como camino inventado paso a paso.

___________

¹ ROSENFELD, Lotty; TALA, Alexia. Sinais dos tempos. Revista ZUM, n. 26, 20 jun. 2024. Disponible en: https://revistazum.com.br/revista-zum-26/sinais-dos-tempos/. Acceso el: 14 ago. 2025.

² G1. Formigas superam humanos em teste de inteligência coletiva; veja vídeo. g1, 17 mar. 2025. Disponible en: https://g1.globo.com/ciencia/noticia/2025/03/17/formigas-superam-humanos-em-teste-de-inteligencia-coletiva-veja-video.ghtml. Acceso el: 14 ago. 2025.

³ Moción de Orden (2002) es una obra de video en tránsito. Comienza con la proyección nocturna de una fila de hormigas que cruza el círculo del helipuerto de una plataforma petrolera en el Estrecho de Magallanes. A partir de ahí, el mismo motivo reaparece en fachadas e interiores, en el metro, en muros y en camiones, además de ocupar el Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, el Museo de Arte Contemporáneo, la Galería Gabriela Mistral y el Centro Cívico de Santiago.No se trata de una película única ni de un objeto fijo: la instalación es recombinante, con múltiples proyecciones, fotografías y fuentes sonoras, siempre ajustadas a la arquitectura del lugar.

Al superponer el enjambre mínimo al aparato del petróleo y a edificios del Estado, la artista introduce ruido en el orden vigente y muestra que los códigos del espacio público pueden ser interrumpidos y rehechos.

Las hormigas operan como metáfora de una multitud que se desorganiza y se reorganiza, inventa rutas frente a los obstáculos y sugiere otros modos de circulación de lo común.

⁴ Las acciones del CADA resuenan fuertemente en el contexto brasileño y en lo que la curaduría de Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin (Queens Museum, 1999) denominó conceptualismos del Sur. Allí, Luiz Camnitzer, Jane Farver y Rachel Weiss distinguieron “arte conceptual” (de corte más formalista, alineada con el minimalismo euro-norteamericano) de conceptualismo, entendido como un conjunto de prácticas que, entre los años 1950–1980, amplía el campo del arte: desmaterializa el objeto (desplazando su sentido y reinvirtiendo significados en objetos y signos preexistentes), practica crítica institucional, se compromete directamente con la vida pública y la política, y enfatiza el lenguaje y la circulación.

⁵ RICHARD, Nelly. La insubordinación de los signos. Santiago: Ediciones Cuarto Propio, 1994.

⁶ FLORES, Mariairis; GIUNTA, Andrea. Arte, género y feminismo en torno al trabajo de Lotty Rosenfeld: conversación. In: LOTTY ROSENFELD: ENTRECRUCES DE LA MEMORIA (1979–2020). Buenos Aires: Parque de la Memoria; Embajada de Chile – Centro Cultural Matta; Fundación Lotty Rosenfeld, 2024. Catálogo de exposición.

⁷ RICHARD, Nelly. Activar la imaginación crítica en torno a los signos: de una sola línea. In: LOTTY ROSENFELD: ENTRECRUCES DE LA MEMORIA (1979–2020). Buenos Aires: Parque de la Memoria; Embajada de Chile – Centro Cultural Matta; Fundación Lotty Rosenfeld, 2024. Catálogo de exposición.

⁸ Extracto de documento perteneciente a la Fundación Lotty Rosenfeld.

⁹ Es posible escuchar la introducción de Batman en el siguiente enlace: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EtoMN_xi-AM

¹⁰ Para saber más sobre la producción de imágenes de la artista: ROJAS, Sergio. El cuerpo de los signos. In: ROSENFELD, Lotty. Moción de orden [catálogo de exposición]. Santiago de Chile: Galería Gabriela Mistral, 2002. p. 4–37. Disponible en: https://repositorio.cultura.gob.cl/bitstream/handle/123456789/5068/Lotty%20Rosenfeld.PDF?isAllowed=y&sequence=1. Acceso el: 14 ago. 2025.

¹¹ Hablando de archivos, vale la pena retomar el trabajo de la Fundación Lotty Rosenfeld (Santiago, 2021). Entidad privada sin fines de lucro creada por los hijos de la artista, la fundación se dedica a conservar, exponer y difundir su obra y sus archivos. El Archivo Lotty Rosenfeld reúne cerca de 25 metros lineales de documentación producida entre 1968 y 2020 (correspondencia con artistas y curadores, registros fotográficos y audiovisuales, proyectos, catálogos y folletos), organizada en un fondo único de la artista. Se trata de un acervo abierto y en expansión, movilizado por exposiciones y proyectos que atestiguan la vigencia y relevancia de su legado. La mayor parte de los documentos utilizados para escribir este texto fueron consultados en la plataforma en línea de la institución. Acceso en: https://fundacionlottyrosenfeld.org/

¹² Para una reflexión sobre el papel del arte en la contemporaneidad, ver breve relato de la artista en: TALA, Alexia. How Chilean Artist Lotty Rosenfeld Created an Enduring Protest Symbol. ArtReview, 13 oct. 2020. Disponible en: https://artreview.com/how-chilean-artist-lotty-rosenfeld-created-an-enduring-protest-symbol/. Acceso el: 14 ago. 2025.

¹³ Extracto tomado del documento Intención de obra 1 – Integrante del acervo de la Fundación Lotty Rosenfeld.

¹⁴ Ver reflexiones sobre este tema en: BRIZUELA, Natalia; BRYAN-WILSON, Julia. Speaking of Lotty Rosenfeld: “Gestures Dangerous, Simple, and Popular”. October, v. 176, p. 111–137, Spring 2021. DOI: 10.1162/octo_a_00429. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1162/octo_a_00429. Acceso el: 14 ago. 2025.

¹⁵ En palabras de la artista: “El neoliberalismo promueve formas de arte que tienden al espectáculo, pienso que lo importante y lo productivo en medio de esta situación es poner en el espacio público producciones artísticas incomodas y rebeldes a las operaciones de mercado.” Extracto tomado del documento Intención de obra 1 – Integrante del acervo de la Fundación Lotty Rosenfeld.